How to recursively make tangent circles inside circles and animate them like JK

See the Pen Recursive Circles III by Johan Karlsson (@DonKarlssonSan) on CodePen.

Some people find circles a fascinating shape. Circles are surrounded by mathematical paradigms. For example: did you know that even if circles are closed curves they still are ruled by one of the most interesting irrational numbers, Pi, which is a transcendental number?

And if you are a fan of circles, why not having several of them, recursively?

This is what JK, or Johan Karlsson, one of my favorites artist in Codepen, did for one of his series for the 2021 edition of Genuary: “Recursive Circles III”.

Questions that I had when looking at his project were:

How did he organize his code?

How did JK manage to get those circles inside other circles?

How did he make the recursion?

And how did he make them rotate in harmony?

In this post I will try to re-verse the code to get some answers to my questions. I will include quick visuals using a carousel and also the canvas API.

I want to share some carousels I found when working on this project (POST IN PREPARATION)

The Code

There are many other more advanced projects about recursivity and circles, but I chose JK’s one because I like his projects and the way he codes. He is usually on the search of striking patterns based on few geometric forms, all with very simple code using vanilla Javascript.

The whole implementation for this project was truly simple: A very simple css, a one-line html and a javascript of just 58 lines of prettified code, including empty lines.

Let’s put some attention to the JS code.

Code Composition and Organization

The code consists of:

- A canvas instantiation function

- Canvas circles using the

arcmethod - Some lines of code to control for the position and rotation of the circles

- Recursive calls of the drawing function, with a clear termination

- A

drawfunction

JK started his code with an instantiation of the canvas:

|

|

The code above includes the declaration of some high-scope variables, the initialization of the canvas instance and the resize function. The code doesn’t have anything extraordinary: it is really standard, simple and organized.

The following is where the animation takes place:

|

|

A magic constant here is the argument related to iterations, which control the depth of the recursions, and have a particular effect on performance (relevant!). He also make use of “magic numbers” to modify the values of the angles when recursively calling the function.

The last function he declared was the draw function, accepting an argument (a time-based one):

|

|

Notice that in the draw function there are more configurations. In particular, there are some “magic numbers”:

- the

shrinkFactor, - one associated to the value of

r, and - another associated to the

angle.

we will discuss them later.

I would rather finish this section by highlighting for such a simple and small script how JK’s code managed to show a couple of good practices, particularly in terms of code organization and readability. His approach seems a minimalistic one, even in his choices for the naming conventions.

In general the code structure selected for this project, as well as other projects by the same author, reminds me a bit the typical organization pattern I have found in many other canvas projects. In particular, it appears to be inspired very much on the typical P5.js pattern:

//variables for color change

let redVal = 0;

let greenVal = 0;

//variable for sun position

let sunHeight = 600; //point below horizon

function setup() {

createCanvas(600, 400);

noStroke(); //removes shape outlines

}

function draw() {

// call sky function

sky();

// a function for the sun;

// a function for the mountains;

// a function to update the variables

}

// A function to draw the sky

function sky() {

background(redVal, greenVal, 0);

}

(From P5.js website (tutorials))

Workflow’s Blocks

By evaluating the final product, you could almost discerned from the code the problems that JK had to solve. We could separate the workflow in 3 different problems, or steps:

- The mathematical problem of inserting circles inside circles.

- The recursive function.

- The animation.

However, maybe because the rush to get his daily project done for the creative coding month, the no-point-to-re-invent-the-wheel, and why not, JK left a few things unexplained in the code. Instead, he resourced to the use of magic shortcuts in the form of pre-calculated values. We would be better able to offer insightful explanations for the workflow if we revealed the origins of such values.

The most important of all of them is the value of shrinkFactor.

shrinkFactor: Solving the “Three circles inside a circle” problem

The project is based on a repetitive pattern consisting in repeatively inserting three circles inside a circle. Probably before starting, JK might had to solve first how to do insert those circles.

The shrinkFactor value is used to re-calculate the size of r of all the inner circles at any recursion. Now, instead of coding the solution to get the value, JK used the result of a mathematical solution. I refer to it as a “magic number” because it is a constant proportion that stay the same for circles of any size. So solving for one gives you a solution you can use for all of them.

Now, to calculate the inner circles he needed to get the position of the centers. Those are the coordinates calculated as (x1,y1), (x2,y2), and (x3,y3). This is done with a code that is repeated for each center. Here is one of them:

|

|

Where r2 might have a misleading name, as it is not a radius but the distance between the center of the outer circle to the center of each of the inner circles.

But how did he come to that value of shrinkFactor?

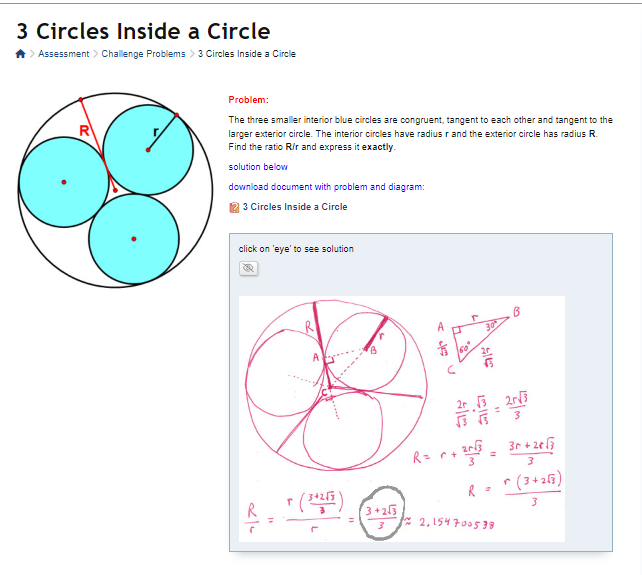

Well… it turns out that it is a very common secondary-school problem. You can find exactly the same problem and its geometric solution by following this link.

Source: thinkib

Source: thinkib

Let’s follow the reasoning step by step:

For our specific case of three kissing circles, the solution to R/r would be:

R/ r = ((3 + 2 * sqrt(3))/3)

which gives the relation between the radius R of the containing circle against the radius r of any of the three inserted circles. For r = 1, the value of R is (approx) 2.155.

Inverting the proportion gives:

r/R = 0.464

which is the value used by JK, probably adjusted to 0.463.

There is another way to get the same relationship by using the Descartes’ Circle Theorem, where, for this particular example, reduces to

(3/r - 1/R)^2 = 2(3/(r^2) + 1/(R^2))

drawPattern function: centers, radii, angles and a couple of other magic numbers

Once he got the constant relations necessary to calculate the inner circles, it should have been easier for JK to draw them.

Every time the function was used, the newR (the radius of the inner circles) was calculated.

Centers were found from the angles, which were 120 degrees (2*PI/3 radians) apart of each other, at a distance of r - newR from the center.

The interation controlled the depth of the recursion (set to 6 in the original project).

But then he also multiplied the angles by other magic numbers at each self call of the drawPattern function. Those numbers were made up and only controlled for different rotation speeds of the circles.

angle is actually the value of the angular speed: the magnitude of the arc that the circle should travel at each frame. The larger that value, the faster it goes.

Those “magic numbers” used by JK had as effect that several different circles rotated under different speeds, also helped by the recursive placing of the different circles.

draw function: setting up the size of the first outer circle and the initial speed of rotation

The “magic numbers” used in the draw function are more mundane and don’t require a lot of discussion. One was used to fit the outest circle to an appropiate size on the screen (the “0.475”). The other one, the 2000 in let angle = now / 2000;, was more a way to initialize the angular speed of the first inner circles.

Tada!

So… What did we learn from this code?

This was a very simple but entertaining project! And what’s more: it didn’t take much to prepare. So it is likely that there will be more posts like this one in the near future.

Particularly because, like this project by JK, there is a lot we can learn from just a few lines of code. And a good bunch of tools we can use to help us reveal their insides.

Final Remarks

For the gallery section showing the maths behind the kissing circles I originally thought to use d3.js and scrollama.js. Then I decided to make an exploration of Konva.js, but, although I liked the use of Konva, just approaching the end of the animations with Konva I found that a carousel was a better fit.

Sometimes a better solution is just the simplest one.

Yes: I wish you happy coding!

The carousel used for this project is the same created by Jemima Abu for Envato TutsPlus in Codepen, with small modifications.

The rest of the code for this project is the same by Johan Karlsson’s, with added controllers using the dat-gui package.

I used Inkscape for the images.